Palestine: A World Cut in Two

How the violence of colonialism lives on today.

“The colonial world,” Frantz Fanon once wrote, “is a world cut in two.”

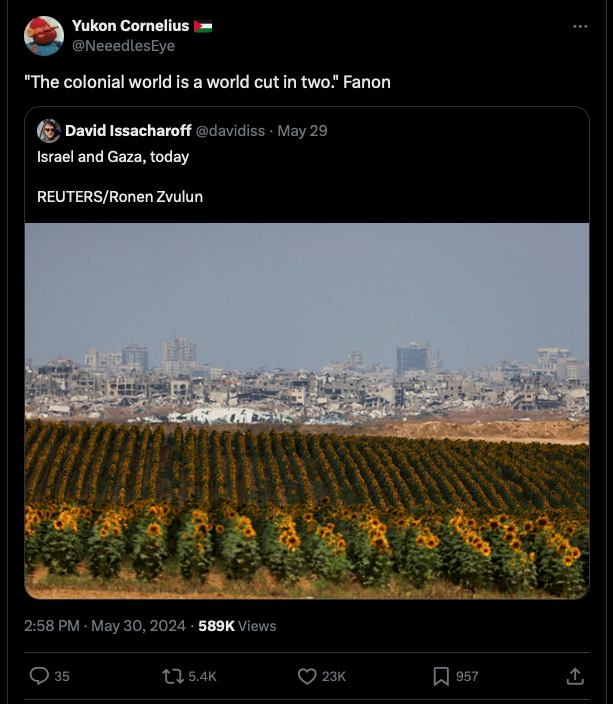

I was recently reminded of these words when I saw a viral photo come by on the platform formerly known as Twitter. The image offers a stark depiction of the immense divide that cuts through the historical lands of Palestine today.

In the foreground lie the lush green farmlands on the Israeli side of the border with Gaza. A field full of sunflowers, all neatly aligned and basking in the glory of a sunny spring day, stretches out into the distance, reaching almost as far as the eye can see.

Beyond it, on the horizon, looms a dystopian hellscape full of bombed-out apartment blocks and crumbling high rises. The buildings that are still left standing stick out like concrete skeletons from the ruins of what was once the world’s largest open-air prison camp—and what has now become an immense urban graveyard.

The UN estimates that more than 10,000 people still lie buried under the 37 million tons of rubble. It could take years to recover their bodies from the wreckage.

Israel’s ongoing assault on Gaza has few parallels in recent military history.1

According to the UN, the death and destruction inflicted by the Israeli army on the occupied Palestinian enclave are “unprecedented in scope and scale.”

More than one in twenty inhabitants of Gaza have been killed or injured since the war began. The daily casualty rate is higher than that of any other 21st-century conflict. The destruction is the worst seen anywhere in the world since the Second World War.

The impact of all this on the civilian population has been incomparable. Almost 90 percent of Gaza’s inhabitants are now internally displaced. Over 1 million people are “expected to face death and starvation” by mid-July. Gaza’s children are living in “hell on earth,” the UN chief has said. And the Israeli massacres show no sign of letting up.

There is now a growing consensus in the international legal community and among the leading scholars of genocide studies that Israel is committing genocide in Gaza.

We have all seen the horrendous images come by on our newsfeeds.

The mangled bodies of unarmed men run over by Israeli tanks. Children shot in the head by Israeli snipers while fetching water for their families. A surgeon dragged out of his operating room and tortured to death in Israeli detention. People with their hands zip-tied behind their backs, summarily executed in a hospital courtyard.

The unrecognizable remains of countless men, women and children buried in shallow mass graves. Charred and incomplete bodies recovered from burnt-out tents in a smoldering refugee camp. A father holding up his headless child. Desperate relatives unable to find, identify or piece together the bodies of their loved ones.

Famished children reduced to tiny little skeletons, sprawled out lifelessly on hospital floors. Women forced to shave their hair as water shortages leave people unable to wash themselves. The lack of clean drinking water causing deadly outbreaks of cholera, hepatitis and other preventable infectious diseases.

The bombing of UN-run schools. The bombing of public hospitals. The bombing of safe spaces where civilians seek shelter. The bombing of farmlands and food supplies. The bombing of critical infrastructure like roads, water pipes and power plants. The bombing of anything required to keep Gaza’s society functioning.

Thousands of Palestinians abducted from their homes and locked away without charge or trial in Israeli detention centers, where they face “systematic torture,” “cruel and sadistic treatment,” and “unimaginable abuses” at the hands of their captors.

The list of atrocities is endless; the full catalogue of horrors too long to recount. It’s a punch to the gut. Every single day. For months on end. Without reprieve.

The acts of violence are so visceral, so extreme and so full of spite that it’s hard to detect a clear rationale behind them other than blind rage and collective punishment.

And yet there’s a method to the madness. All this wanton brutality is clearly designed with a purpose in mind. To make life in Gaza unbearable. To break the morale of the civilian population. To remove all prospects of peace and reconciliation. To force the Palestinians to once again pack up their bags and leave their homelands behind.

All the evidence now points in this direction. The blocking of humanitarian aid. The cutting off of water supplies. The massacres of civilians waiting for food assistance. The closing of all border crossings with Israel and now also with Egypt in the South. The fact that people in the North are made to subsist on just 245 calories a day.

It all fits into a pattern. The killing of journalists to prevent the truth from getting out. The smearing of UN agencies to prevent humanitarian aid from coming in. The deliberate targeting of NGO workers to scare away international organizations and leave the people of Gaza trapped, isolated and completely on their own.

These are not accidents. Netanyahu and his extremist settler friends know what they are doing. They are open about it: all we have to do is listen to what they are saying.

They no longer want their colonial world to be cut in two. They want to obliterate the other side and establish total control. They want to expel the remaining inhabitants, move in Jewish settlers and annex Gaza to execute their dark vision of a Greater Israel.

They are coming for the Palestinian land. And this time, they want it all.

At heart, the struggle between the colonizer and the colonized is always a struggle for the land. “Earth hunger,” is what it’s been called: the lust for territorial expansion that drove European imperialists and their settler-colonial descendants to conquer or colonize up to 80 percent of the world’s landmass between 1492 and 1914.

This furious territorial expansion could not be sustained in the long run. Europe’s globe-girdling empires eventually gave birth to their own grave-diggers. Starting with the Haitian Revolution, European control was rolled back in successive waves of decolonization that culminated in the independence of 80 new countries after 1945.

For a long time, people in the West assumed that that was the end of it. When the last vestiges of settler-colonial rule were mopped up with the fall of apartheid in South Africa in 1994, it was said to be done. We now lived in a postcolonial world. A single world. A globalized world. Unequal, perhaps, but largely free and undivided.

It was always a myth. The violence of colonialism did not end with the fall of the European empires or the end of apartheid in South Africa. It’s still with us today. It remains an open wound. A material reality. An enduring structure of oppression and marginalization that continues to shape the lives of millions of people in the present.

The Palestinians know this reality all too well.

Today, Israel’s illegal occupation and its systematic denial of Palestinian freedom represents the unfinished business of decolonization. Here, Fanon’s words continue to ring true: the colonial world of Israel and Palestine remains a world cut in two.

Nothing represents this rift more viscerally than the 700-kilometer-long separation barrier that runs like a scar through this ancient Levantine landscape.

Today, it’s easy to criticize the belligerent nationalism of Benjamin Netanyahu and the messianic extremism of his settler-colonial coalition partners for the systematic violation of Palestinian rights. But the separation barrier that cuts Israel and Palestine in two was actually the brainchild of the Labour Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, a supposed moderate who was later murdered for his role in the Oslo peace process.

In 1994, the same year that apartheid ended in South Africa, Rabin declared that “we have to decide on separation as a philosophy. There has to be a clear border.”

What Rabin was calling for was Hafrada, the Hebrew word for separation. The Afrikaans word apartheid, of course, has the exact same meaning: it refers to a state of separation, a state of being apart. Hafrada is Israel’s own form of apartheid.

“This path must lead to a separation,” Rabin later reiterated, “though not according to the borders prior to 1967. We want to reach a separation between us and them.”

Rabin’s words did not go unheeded. In 2002, at the height of the Second Intifada, Ariel Sharon’s right-wing government began construction work on the massive concrete barrier and border fence that now separates Israel and occupied East Jerusalem from large parts of the West Bank.

This separation barrier has rightly become known as the “apartheid wall.”

The wall does not just set the Israelis apart from the Palestinians. It also separates the Palestinians from their own land. Around 85 percent of the barrier is built inside the West Bank. Here, it cuts Palestinian farmers off from their fields, shepherds from their grazing grounds, workers from their workplaces, and families from each other.

To get to their land or to work on the other side, Palestinians need special permits to pass through one of the heavily militarized gates in the wall, where they are subjected to long waits, thorough checks and daily humiliations before they are allowed through.

The apartheid wall, illegal under international law, stands as a physical testament to an entire system of racial segregation. But it’s also accompanied by a much less visible set of laws that are deeply encoded into the DNA of the Israeli legal system.

To begin with, there’s the controversial Nation-State Law that defines Israel as a nation-state belonging exclusively to its Jewish citizens. “The right to exercise national self-determination,” it says, is “unique to the Jewish people.”

This despite the fact that the country has a large minority of two million Palestinians with Israeli citizenship, who constitute more than 20 percent of the population.

These “Arab-Israelis”—really indigenous Palestinians descended from those who refused to leave their homes after finding themselves trapped on the Israeli side of the armistice line in 1949—have long been subjected to an extensive system of legal discrimination.

Israel currently has more than 65 laws that explicitly discriminate between Jewish-Israelis and Palestinians with Israeli citizenship, effectively turning the latter into second- or third-class citizens on their own historical homelands.

Today, there is a widespread consensus in the human rights community that Israel is, indeed, an apartheid state. Palestinians and South Africans have long recognized this reality, of course, but in recent years leading UN officials and major human rights organizations such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and the Israeli advocacy group B’Tselem have belatedly come around to the realization as well.

It’s hard to deny. The logic of apartheid is so starkly inscribed into the landscape and so deeply embedded in the law that there’s no longer any real debate on the question.

If Israel actively discriminates against its own Palestinian citizens, it treats the Palestinians on the other side of the separation barrier with even more contempt.

The apartheid wall that cuts through the West Bank has really only ever run one way: it’s meant to keep Palestinians out of Israel, but not Israelis out of Palestine.

In fact, the Israeli government has long promoted an aggressive settlement program to illegally populate the occupied Palestinian territories with Jewish-Israeli settlers.

Again, it was a “moderate” Labour government that made the first moves in this direction. After the Six Day War of 1967, the so-called Allon Plan called for the creation of a security perimeter around Israel. This informed the decision to annex East Jerusalem and start establishing a presence of Israeli settlers in the West Bank.

The first settlers were mainly secular laborite Zionists, but subsequent Likud governments radicalized the settler-colonial project by moving in religious Zionists. These messianic extremists dreamed of actualizing their own Biblical vision of Eretz Israel: a greater Jewish state with borders stretching “from the river to the sea.”

As of last year, there were 144 state-backed Israeli settlements and more than 100 unofficial Jewish outposts on occupied Palestinian land. Their population has steadily increased over the past decades. Almost 500,000 Israeli settlers now live on occupied land in the West Bank, while another 220,000 have colonized parts of East Jerusalem.

All of this is in flagrant violation of the Geneva Convention, which forbids occupying powers from transferring their own civilian populations onto occupied territories.

But here, too, there is actually a method to the madness.

The short-term goal of the settler-colonial project is to entrench Israel’s spatial dominance over the Palestinians living in the West Bank.

The long-term goal is to shatter the Palestinian territories into small and disconnected parcels and thereby undermine the viability of a future Palestinian state.

The settlements are also meant to create “facts on the ground,” which will eventually ease the annexation of large parts of the West Bank into a Greater Israel.

A quick look at the map reveals what this settler-colonial geography looks like in practice. Israeli settlements (in red) pockmark large parts of the West Bank, leaving the Palestinian-controlled occupied territories (in green) completely fragmented:

What does this settler-colonial geography look like on the ground?

Imagine, once more, a world cut in two.

On one side, we encounter the quiet suburban idyll of some of the Israeli settlements: full of well-built, affordable houses with neatly manicured green lawns.

“It’s so easy to live here,” one Israeli settler recently told the Wall Street Journal.

On the other side, we encounter Palestinian villages surrounded by roadblocks and military checkpoints, long lines of people waiting behind barbed-wire fences, forced to go undergo elaborate inspections before they're allowed to get on with their day.

It all recalls Fanon’s description of the colonial geography of French-ruled Algeria.

In his classic book, The Wretched of the Earth, The Martinican psychiatrist and anti-colonial thinker powerfully captured the divided essence of this colonial world.

“The settler’s town,” he observed, “is a strongly-built town, all made of stone and steel. It is a brightly-lit town; the streets are covered with asphalt, and the garbage-cans swallow all the leavings, unseen, unknown and hardly thought about … The settler’s town is a well-fed town, an easy-going town; its belly is always full of good things. The settler’s town is a town of white people, of foreigners.”

“The town belonging to the colonized people,” by contrast, “is a place of ill fame, peopled by men of evil repute … The native town is a hungry town, starved of bread, of meat, of shoes, of coal, of light. The native town is a crouching village, a town on its knees, a town wallowing in the mire. It is a town of niggers and dirty Arabs.”

What divides these two worlds is an oppressive system of racial segregation.

“This world divided into compartments, this world cut in two,” Fanon writes, “is inhabited by two different species. When you examine at close quarters the colonial context it is evident that what parcels out the world is to begin with the fact of belonging to or not belonging to a given race, a given species.”

The effect of this racial segregation, Fanon remarks, is that it “dehumanizes the native, or to speak plainly it turns him into an animal. When the settler seeks to describe the native fully in exact terms he constantly refers to the bestiary.”

We can clearly see this logic of dehumanization at work in Israel and Palestine today.

In Israeli public discourse, the Palestinians are frequently referred to as “animals,” “rats” or “snakes.” Former Prime Minister Ehud Barak even called them crocodiles: “The more you give them meat, the more they want.” He also called Israel a “villa in the jungle,” implying that those who live outside its walled gardens are wild beasts.

History teaches us the dangers of treating other humans like animals. Over time, the logic of dehumanization can become a prelude to genocide and extermination.

This is precisely what is happening in Gaza today.

As the Israeli defense minister Yoav Gallant ominously put it on the eve of the Gaza genocide, “we are dealing with human animals, and we will act accordingly.”

By cutting the world in two, by constantly setting the colonizer up against the colonized, by constantly dehumanizing the “native” in the eyes of the settler, the colonial project inevitably breeds an escalating cycle of violence.

As Fanon pointed out, this cycle always begins with the soldier and the policeman: the personifications of the occupying power. But it doesn’t end there.

The colonial world is marked by its own peculiar micro-aggressions, its own rhythms of ritualistic abuse and humiliation, that go well beyond the violence of the state.

Much of this everyday violence actually comes from the settler himself.

Fanon had seen this first-hand in colonial Algeria. The settler, he observed, “is the bringer of violence into the home and into the mind of the native.”

Today, the Israeli settler uproots the Palestinian’s olive trees. He kills, steals or chases away his livestock. He burns his mosque, vandalizes his property, damages his home, terrorizes his family. When he can, he will simply take what he considers to be rightfully his, dispossessing the Palestinian of his land, his dwellings, his possessions.

Most of the time the Palestinians have no choice but to suck it up. The settler is often armed, and he knows that he can count on the support of the police and the army.

Everything here therefore promotes a culture of settler impunity.

Once again, the divisions in this colonial world are stark. On one side, the settlers fall under Israeli civilian law: they share all the same rights and protections as ordinary Israeli citizens. On the other side, the Palestinians fall under military rule. They have no civil rights, few opportunities to go to court, and no army or police to protect them.

With the full weight of the colonial state behind them, the settlers become increasingly brazen and aggressive, increasingly troublesome and cruel.

For the Palestinians, then, violence is always around the corner. They know that a soldier or a settler can shoot them on sight, anytime, without legal repercussions.

Just walking down the street, traveling home from work, getting some fruit from the market, taking the sheep out into the fields, doing some construction work on the house—all of these daily activities now become fraught with danger.

Being a woman or a child offers no special protections in this regard. In the eyes of the settler, the Palestinian is always already guilty. It’s her existence that’s the problem.

The mere fact that the Palestinian still lives on her own land now becomes an affront to the settler. He would rather have her gone—dead or alive—and he will try everything in his power to make that happen.

In practice, the settler therefore reigns with impunity over the lands of the “native,” while the “native” lives under total military control and in constant fear of the settler.

It is a well-documented fact that settler violence against Palestinians has been rising for years. Even before the Hamas attacks, the first eight months of 2023 were the most violent on record. After October 7, things have only gotten exponentially worse.

Since then, the army has called up 5,500 settler-reservists and assigned them to “regional defense battalions” in the occupied West Bank. The state then distributed over 7,000 guns to these battalions and to “civilian security squads” in the settlements.

As a result, settler violence in the West Bank has exploded over the past months. Between October 7 and mid-April, the UN recorded more than 700 violent settler attacks on Palestinians. In nearly half of these incidents, the army was present.

Israeli soldiers and armed settlers have killed almost 500 Palestinians since October 7.

The worst part is that there is no prospect of this violence abating anytime soon. The messianic Zionist settlers who carry out most of the attacks have taken over the government. As Netanyahu’s coalition partners, they now effectively control the state.

Bezalel Smotrich, a far-right extremist who was arrested in 2005 for trying to derail the withdrawal of Israeli settlers from Gaza, is now Israel’s finance minister and the man in charge of the West Bank. Itamar Ben-Gvir, who has been convicted several times for supporting terrorist organizations, is now Israel’s national security minister.

These are the men responsible for shaping the future of Gaza and the West Bank. And they are extraordinarily candid about their political objectives.

Bezalel Smotrich has said that he is committed to “imposing sovereignty on all Judea and Samaria,” using the old Biblical name to refer to the Palestinian territories in the West Bank. “In this way,” he explained, “we will be able to create a clear and irreversible reality on the ground.”

Itamar Ben-Gvir has simply called on Israelis to “run for the hilltops, settle them.”

Benjamin Netanyahu, for his part, claims that the Jewish people have “an exclusive and indisputable right to all areas of the Land of Israel,” including the West Bank.

The coalition agreement of Netanyahu’s government declares that “the Prime Minister will lead the formulation and implementation of policy within the framework of which sovereignty will be applied to Judea and Samaria.”

Nor do Israel’s territorial ambitions halt at the West Bank. Gaza is next in line.

Itamar Ben-Gvir has openly stated that he would be “very happy to live in Gaza” when the war is over. If “hundreds of thousands” of Palestinians “voluntarily leave” the area, the security minister elaborated, “we will be able to bring in more and more people.”

It should be obvious by now that neither Israel’s extremist settlers nor its supposed “moderates” have any real interest in a just peace. They all want the Palestinian land—and the extremists will go to any lengths to get it. This is the wellspring of the horrific cycle of violence we see in the occupied Palestinian territories today.

Yet, as Fanon pointed out, the cycle of violence never ends there. Eventually, it always comes full circle. Eventually, the violence always blows back onto the settler himself.

The settler can build concrete walls and steel fences around his pretty little lawn and create his own make-belief paradise on stolen land, he can presume himself safe and firmly in control of the state, but the violence of the occupation, once released from its wellspring, can never be contained. It always comes back to haunt him in the end.

“That same violence,” Fanon writes, “ will be claimed and taken over by the native.”

One day the pent-up frustration, the compounded trauma, the endless humiliations, the deep sense of loss and the constant dehumanization—one day all of this simply comes flooding back. The “native” rises up. The “dirty Arab” fights back.

At that moment, Fanon ominously remarked, “he surges into the forbidden quarters.”

These chilling lines from The Wretched of the Earth are probably among the hardest to read today, after the horrific violence of October 7. They are haunting. Yet they are also frequently misread as a glorification or prescription of violence.

In reality, Fanon did not glorify or prescribe violence. Nor did he see any point in condemning it. Violence was already everywhere in colonial society. Fanon wanted to understand it. As a psychiatrist who had treated countless traumatized Algerian independence fighters, he tried to offer a diagnosis of where the violence came from.

The root of the problem, Fanon concluded, lies in the colonial system itself. In his practice, he realized that the violence of the colonizer eventually finds its way into the minds of the colonized. There it festers and produces visions of violent retribution. It is only a matter of time before the “native” acts out on this visceral desire for revenge.

“Terror, counter-terror, violence, counter-violence,” Fanon wrote: “that is what observers bitterly record when they describe the circle of hate.”

The point of the anti-colonial struggle, then, is not to perpetuate the cycle of violence, but to end it. If the origin of the problem lies in the colonial system itself, it follows that the only way to end the bloodshed is to end the occupation that gave rise to it.

Here, Fanon made another observation that resonates today.

“In all armed struggles,” he wrote, “there exists what we might call the point of no return. Almost always it is marked off by a huge and all-inclusive repression which engulfs all sectors of the colonized people … Then it [becomes] clear to everybody, including even the settlers, that ‘things [can’t] go on as before’.”

We can observe this dynamic in many anti-colonial struggles: from Mau-Mau to Jakarta, from Angola to Algeria. In each of these episodes, the all-out repression of the colonial state was not a sign of strength, but a sign of weakness. The bloodshed was horrendous, but it did not take long for the colonial system to be dismantled.

Have Israel and Palestine now arrived at a similar point of no return?

Some experts, including the critical Israeli historian Ilan Pappé, believe this may well be the case. I personally feel that it’s still too early to tell. But either way it seems to me that the answer to this question no longer lies in the Middle East itself.

As long as Israeli hard-liners maintain the upper hand over the Palestinian factions and the active support of the West, they will continue to try everything in their power to drive the Palestinians off their own land. Nor should we count on the wisdom of the so-called “moderates,” who have actively supported the occupation at every turn.

I believe that the ball now lies in the court of the West—and above all with the United States. Will the US government continue to arm the Israeli settlers and support the genocide in Gaza? Will it continue to underwrite apartheid inside Israel and settler-colonialism in the occupied territories of East Jerusalem and the West Bank?

Or will it finally bring the settlers to heel and call a halt to the circle of hate?

These are the questions that will determine the future of the Middle East. That’s why, in my next posts, I’ll be zooming out from Israel and Palestine to refocus the attention on the West’s own role in supporting the ongoing genocide in Gaza.

To begin with, I have an essay coming out in the New Statesman this week in which I take a closer look at Western hypocrisy on Israeli war crimes and the recent obsession with the so-called “rules-based international order.” I’ll share it here when it’s out.

Thanks for reading this long post. I started The Rift because I care about the issues I write about. If you care about them, too, please help me spread the word by forwarding this essay to some of your friends. You can also support the project by upgrading to a paid subscription:

I left out most sources to avoid overburdening the text with footnotes or hyperlinks. If you’d like to see evidence for (or further reading on) any particular facts or claims, please send me an email and I’ll be happy to provide you with the relevant sources.